Plants need a system to carry water and nutrients from the roots to the leaves and back again. This system consists of two types of tissue: xylem and phloem. We can see them as the “veins” running through leaves. These tissues are called “vascular tissues” because they have tiny tubes, or vessels (vascular comes from the Latin for “vessels”), that carry water and sap.

There is a group of plants that do not have xylem and phloem, but they must necessarily remain very small so that all the parts of these plants can remain close to water. These are called “nonvascular plants.” Mosses are probably the most familiar members of this group. In contrast to these tiny nonvascular plants, plants “with vascular tissue are capable of growing much larger because they transport the necessary water and nutrients throughout the entire plant. These plants also have well-developed roots, leaves, and stems.”[1]

In all kinds of plants, life-sustaining food is made in the leaves by photosynthesis. Chloroplasts in the leaves capture electromagnetic energy from sunlight and convert it into chemical potential energy in sugars. In vascular plants, sugars then travel through the phloem, which “consists of networks of tubules that run throughout the plant,”[2] so that all the cells in the plant have energy to carry out the tasks that let the whole plant live and grow. Photosynthesis requires water, which is brought up into the plant from the roots through the “hollow tubes” of the xylem. “In trees, water rises vertically at a rate of up to 150 miles per hour!”[3]

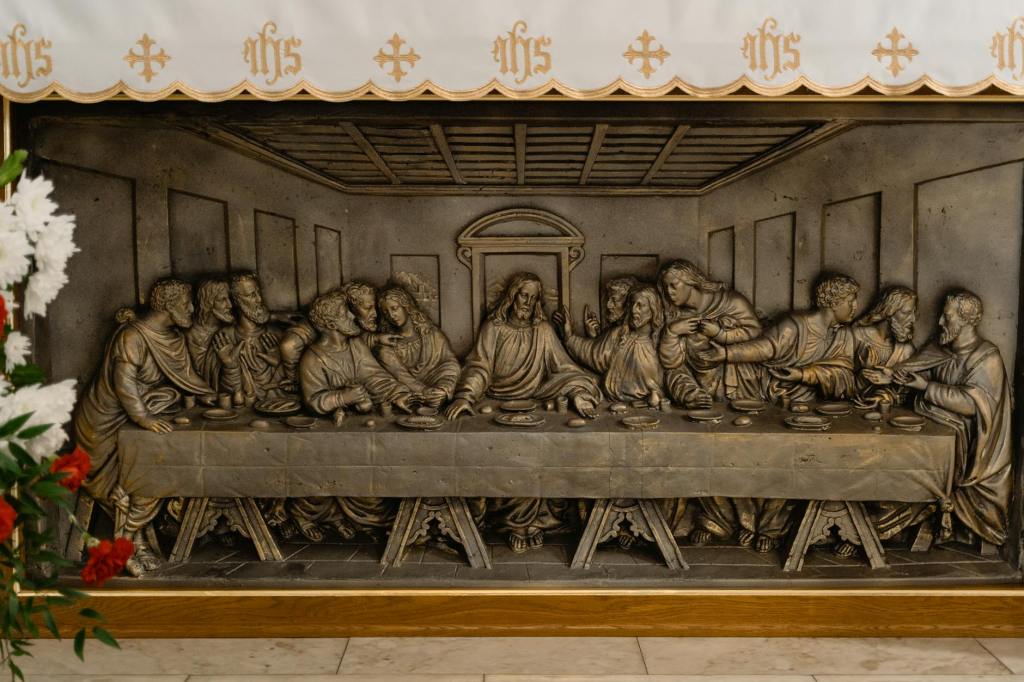

The Catholic Church is like a vascular plant. In the Church, the life-giving energy comes from Jesus Christ, who is like divine photosynthesis. In the Eucharist, God’s invisible light and love are “captured” (or rather, voluntarily given) and transformed into a form that we can receive, as the energy from sunlight is captured and transformed into sugars in the chloroplasts of the leaves. At the Last Supper, Jesus commissioned His Apostles to continue to offer the Eucharist (“Do this in remembrance of me,” Luke 22:19, RSV-SCE) so that His saving Eucharistic presence could remain always in the Church and reach to believers all around the world. The Apostles also took care to appoint successors—bishops—so that God’s life in the Eucharist could reach through time as well:

“[T]he risen Christ, by giving the Holy Spirit to the apostles, entrusted to them his power of sanctifying: they became sacramental signs of Christ. By the power of the same Holy Spirit they entrusted this power to their successors. This ‘apostolic succession’ structures the whole liturgical life of the Church and is itself sacramental, handed on by the sacrament of Holy Orders.” (Catechism of the Catholic Church 1087)

The bishops, as the successors to the Apostles, are the primary conduit of Christ’s life to the whole Church. Apostolic succession is like the xylem and phloem running through the “vascular plant” of the Church, making sure that every part of the “plant” has what it needs to live and grow.

Bishops also eventually appointed priests to help them. Our connection to our bishop is usually maintained through our connection to our parish priests. During the holy sacrifice of the Mass, in the gesture of epiclesis, the priest or bishop asks the Holy Spirit to come down on the gifts of bread and wine to transform them into the body and blood of Jesus Christ. This gesture evokes the action of the xylem in bringing life-giving water into the plant, which is a necessary ingredient for photosynthesis. The transubstantiation of the bread and wine is like the actual photosynthesis, and the distribution of the Eucharist from the hands of the celebrant to the faithful in Holy Communion is like the transportation of the sugars through the phloem to the rest of the plant. The availability of the Eucharist is ultimately dependent on the presence of a bishop because he “is ‘the steward of the grace of the supreme priesthood,’ especially in the Eucharist, which he offers or causes to be offered, and by which the Church continually lives and grows” (Lumen Gentium 26).

As individual Christians, we must stay connected to the “plant” that is the Church so that we can receive the life of Jesus. The parable of the True Vine helps us understand the dynamics involved here. Jesus says:

“Abide in me, and I in you. As the branch cannot bear fruit by itself, unless it abides in the vine, neither can you unless you abide in me. I am the vine, you are the branches. He who abides in me, and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit, for apart from me, you can do nothing.” (John 15:4-5)

Additionally, entire Christian communities need to stay connected to the apostolic succession found in the Catholic Church to ensure their access to the divine power that Jesus entrusted to His Apostles and their successors. When Protestant Christians broke away from the Catholic Church, they lost this vital connection and became like separated branches in danger of withering and dying (John 15:6). Thankfully, reconciliation and reconnection are always possible, such as the #Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter (Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter | Mission of the Ordinariate | Houston, Texas) providing a way for entire communities of Anglican Christians to become Catholic.

Let us take care to pray for and obey our bishops since “Christ himself chose the apostles and gave them a share in his mission and authority….He continues to act through the bishops” (CCC 1575). Then the entire “plant” of the Church can grow and flourish, bringing God’s life to the entire world, thanks to the xylem and phloem of apostolic succession.

[1] Heather Ayala and Katie Rogstad, General Biology (Camp Hill, PA: Novare Classical Academic Press, 2020), p. 238.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

Leave a comment